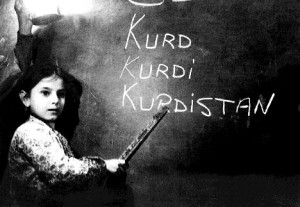

No language, no life

Sweet freedom, everyone is looking, so come here

Sweet freedom, everyone is looking, so come here

Sweet freedom, our eyes are tired because we have been looking for so long

Mihemed Şexo, a legendary Kurdish musician, sang this song with as much longing for freedom as his ardent listeners, a people oppressed by Syria, Turkey, Iran and Iraq. He continued to sing and distribute records in Kurdish despite repeated harassment by the Syrian security police. He was known not just for his love songs for Kurdistan, but also his courage in defending his language in the face of an oppressive regime.

The struggle for the right to freely speak Kurdish continues and the demand for mother tongue education is subject of an ongoing debate in Turkey. Turkey’s constitution recognises only Turkish as the official language and it is therefore not possible for Kurds to receive education in their mother tongue, though elective courses in Kurdish are permitted. This is in spite of the fact that Kurds make up roughly 25% of the population in Turkey and that mother tongue in education has a beneficial effect on the student: they make a better start when they begin in school, they have increased self-confidence and they perform better than those who have to learn a new language when they start in school. Education in mother tongue is also key in preserving one’s culture and help it to develop and be strengthened.

Article 42 of Turkey’s constitution states the following:

No one shall be deprived of the right of learning and education.

The scope of the right to education shall be defined and regulated by law.

Training and education shall be conducted along the lines of the principles and reforms of Atatürk, on the basis of contemporary science and education methods, under the supervision and control of the State. Institutions of training and education contravening these provisions shall not be established.

The freedom of training and education does not relieve the individual from loyalty to the Constitution. […]

No language other than Turkish shall be taught as mother tongue to Turkish citizens at any institutions of training or education. Foreign languages to be taught in institutions of training and education and the rules to be followed by schools conducting training and education in a foreign language shall be determined by law. The provisions of international treaties are reserved.

One of Atatürk’s reforms was the assimilation policy that was carried out against Kurds which included banning the Kurdish language and impeding their education. A Minister of National Education from Atatürk’s time, Necip Bey, said then: “Do we want today’s armed Kurds to appear before our children tomorrow as intellectuals?”

It is telling that Turkey’s educational system in 2014 is based on a chauvinistic and discriminating article in the constitution that upholds Atatürk’s principles of Kurdish inferiority.

There have been made some concessions since the present ruling party AKP came to power in 2002, but they are far from sufficient and are rather parts of a political game aiming to improve relations with the European Union and its own image than signs of respect for human rights.

International laws and treaties state that education in one’s mother tongue is a human right, e.g. the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966 that was signed and ratified by Turkey while still maintaining reservations. It opened up for minorities to receive education in their mother tongue but seeing as Turkey does not recognise Kurds as a minority like Jews, Armenians and Greek due to the Lausanne Treaty from 1923, Kurds are not allowed to receive mother tongue education. But even the aforementioned groups are restricted in their rights as they receive no state funding.

No life without language

On February 21, people all over the world celebrated the International Mother Tongue Day. Meanwhile, Kurds were demonstrating in the streets, demanding that the Turkish government allows education in their mother tongue. Slogans like “There will be no life without language”, “Our language is our existence” and “Multi-language empowers humanity” were chanted in Kurdish, once again voicing their demand of mother tongue education.

A few days later officials from the Ministry of Education allegedly demanded a list of teachers who had given classes in Kurdish on February 21, after an organisation of educators by the name Eğitim-Sen encouraged public school teachers to conduct two hours of the class in Kurdish. bianet reported that the Ministry sent out this directive:

In order to be used in a processing, we are demanding the list of teachers who were teaching in Kurdish in public schools and the approved photocopies of class logs on February 21, 2014…

What is the ministry going to do with this list? Will they frame it and hang it on a wall because they applaud the initiative and welcomes the Kurdish language in the classroom or will they arrest the teachers on charges of threatening Turkey’s territorial integrity and imprison them indefinitely and postpone their trial time after time so they are left to rot like so many other Kurdish political prisoners?

Kurds are tired of waiting for the government to allow education in mother tongue, tired of waiting to be “granted their rights.” It is a worn-out saying but it is true that a right delayed is a right denied.

That is why residents in the Kurdish Yalaza village in the province of Amed (Diyarbakir) built a school that will start Kurdish education in April.

“Our demand of a Kurdish school and education in our mother tongue are one of the main legs of the democratic nation paradigm,” Pınar [a teacher] said, adding that is how the autonomy will start. “We don’t expect anything from anybody. This school was built entirely by the people’s will and gathering money among themselves.”

Another example of the people’s initiative is re-naming Turkish streets in cities like Amed and giving them Kurdish names. One man, İzettin Akkuş, said: “We know and understand Kurdish. When the names of the streets are Turkish, we cannot meet [in] them.”

Cuma Fincancan said: “[Turkish] names of the streets, avenues and villages are being used for years. Our own language is not developing with this application. Our language lagged behind. Therefore, the more we speak Kurdish, it will be better.”

These are people’s initiatives, not the Turkish government’s initiatives who have offered the Kurds nothing but superficial reforms like Kurdish language education in expensive private schools that most Kurdish families are unable to pay for. This is just one reason why the Turkish Foreign Minister did not deserve applause when he on Tuesday spoke Kurdish at a forum in the Kurdistan Regional Government as he is a representative of Turkey’s government that refuses to allow education in Kurdish. The Foreign Minister’s greeting in Kurdish does not have any significance for school children or families who are affected by the lack of education in mother tongue. The benefit is merely political with a total disregard for any potential social impacts that can improve the situation of Kurdish rights in Turkey.

Let us not be blinded by political agendas. What do the Kurdish people want: to speak their own language or listen to a Turkish Minister speak it?

The Alliance for Kurdish Rights aims to amplify diverse Kurdish voices. Views expressed by our authors and contributors are not necessarily our own. We welcome constructive and respectful feedback and discussions. If you’d like to contribute to AKR, join us.

Comments

Thanks so much for writer

the title like no woman no cry

No language, no life